Background

The McCain Institute and Action for Democracy hosted a tabletop workshop in Warsaw, Poland, from April 3 to 4, 2025, for democracy, civic, and media representatives from Georgia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. This workshop targeted these countries, given their experience as backsliding or threatened democracies in the region, with the goal to share experiences, lessons learned, and tactics for success. All four countries had relatively healthy democracies before descending into illiberal strongman rule, while Poland served as a positive case study and model for solutions on how to reverse such backsliding, at least for now.

Autocrats successfully share tactics and lessons with one another to subvert democracy, passing on a playbook of specific actions we have seen repeated in multiple countries. The infamous “foreign agents law” passed in 2012 in Russia to suppress civil society, for example, has been copied and adopted in Georgia, Slovakia, and other countries. It is reported that advisors to Hungarian leader Viktor Orban advised Georgia’s Georgian Dream party leaders on election manipulation and propaganda tactics ahead of the 2024 elections in Georgia. Authoritarian regimes like Russia also notoriously engage in malign influence operations through financing political parties and actors, election interference, and disinformation campaigns to help up-and-coming strongmen and their political forces. The Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) regularly brings far-right illiberal leaders together to coordinate efforts and build a blueprint for rule, and Orban has frequently shared his recipes there.

Meanwhile, democrats have been slower to collaborate and learn from one another, though activists routinely request such tactical and moral support. Civil society and media representatives have expressed a desire for a space to learn from other like-minded democrats facing similar challenges in the region and build a cross-country network.

The focus of the first day of the workshop was on addressing the problem, including the demand side of rising autocracy – the public’s desire for illiberal regimes and strongman leaders helped by disinformation, manipulation of the concepts of nation and tradition, and fear tactics. By assessing trends across countries, participants discussed shared tactics used by governments to subvert democracy and identified common risks. The workshop then shifted to focus on creative, successful civil society and independent media activities in the face of shrinking space, with the aim to inspire others and encourage possible replication. On the second day, the workshop turned to scenario planning first through the game NewsQuest, which generated real-life situations and possible responses, and then through a World Café exercise where participants rotated through different identified challenges facing democratic activists to harvest solutions and actions. Finally, an expert provided professional training on social media outreach and fundraising, a challenge identified by the participants.

This report aims to highlight several successful interventions and learnings from the workshop in order to build a community of best practices and inspire others.

State of Play: Trends and Risks

Before launching into solutions, participants first discussed several of the big-picture drivers for far-right, anti-democratic movements in Europe and the “appeal of the strongman.” Interestingly, there were few differences between countries in this conversation, with representatives describing cultural-values cleavages, income inequality, democracy’s failure to deliver, grievance politics, and information disorder as some of the shared trends and risks.

In answer to the question of what makes the far-right autocratic movement popular, a participant from Hungary described the lack of an alternative political option, the mobilization of traditional non-voters and young voters, and the manipulation of national identity and religion. A Slovakian activist agreed that the opposition in her country had failed to present a united message and reach outside the capital. She added that autocrats are often skilled communicators, offering simple populist messages and “Robin Hood” solutions to complex problems. Other participants added that the opposition parties were often “arrogant” and “out of touch” with poor and uneducated voters, who made up the base of the far-right.

The group also discussed the hijacking of four important areas by autocrats – patriotism, faith, culture, and tradition. Participants from all four countries agreed that their leaders had manipulated their national narrative, painting a picture of a country with one dominant ethnic and religious group – the “true” citizens – and demonizing anyone who was different as “other.” Through this approach, strongmen create pecking orders of power and privilege — with women, sexual, racial, and religious minorities, and immigrants at the bottom — and divide society. Rewriting history helps such regimes erase any tradition of multiculturalism, tolerance, and equality. Participants agreed that democrats needed to reclaim the national narrative. A Slovakian participant, for example, reported that an effective tactic of the opposition there was the “week of the Slovak flag” to reclaim patriotism.

The conversation also provided foresight to the countries whose backsliding was more recent. Polish and Hungarian participants, for example, shared what could be expected next in the autocrat playbook for Georgia and Slovakia, such as a new broadcasting law and restrictions on universities. The Georgians described how following the implementation of the foreign agents law in their country, the Georgian Dream regime decided it was not enough and passed additional legislation broadening the charge of “treason” and requiring all foreign donations to be first approved by the government. The Slovakian government has just passed a foreign agents law there, so the Slovakian participants took note of what may come next based on the Georgian experience.

Strengthening Responses: Case Studies

Participants had endless creative, unique initiatives to share, as well as an honest assessment of some activities that were less successful (and the learning from that), to address the democratic decline in their countries. This report will highlight just a few of these stories that fall under important thematic lessons: get creative, reach youth, lawyer up, confront, separate religion and state, and get out of town.

Get Creative: Rent a Train

The civic association Mladi in Slovakia launched the Youth Against Fascism Initiative to increase the number of voters in the country’s 2024 presidential elections through three methods: online communication through social media, offline communication at Prague’s main train station, and, subsequently, organizing an election train to Slovakia so students studying abroad could vote.

The online campaign was a success, much of it due, according to organizers, to the smart selection of messengers to reach target audiences. For example, one video featuring senior citizens speaking in simple language and reacting to disinformation related to the presidential campaign became the most viral political campaign video ever produced in Slovakia. It accumulated 3.8 million views in Slovakia and spread to the Czech Republic as well. In total, the online campaign reached approximately 70 percent of all Facebook users and 90 percent of all Instagram users in Slovakia.

The Prague train station campaign featured a banner in the center of the station with the Czech slogan: “Řekněte Slovákům ať jdou volit, když se to podělá, už se domů nikdy nevrátí.” (“Tell the Slovaks to go vote—if it goes wrong, they’ll never return home.”) Employing such humor attracted attention, with viewers sharing it organically on social media, reaching Slovak and Czech audiences. Ultimately, this banner reached more than 1,000,000 people through media coverage.

Finally, the campaign organized an election train to transport primarily students from the Czech Republic to Slovakia to participate in the 2024 elections. Many Slovak students study in Prague, presenting financial and time burdens for voting. The government also eliminated the process of applying for voter ID electronically, requiring an additional trip for many citizens to register to vote. Pre-election polling predicted a low turnout for young voters — according to Ipsos, only 45 percent of young voters expressed interest in voting compared to three-quarters of older voters.

The train had a free registration process with seats first reserved for students, followed by a first-come, first-served basis for non-students. Together with two buses, the train transported over 800 people to vote. Importantly, the train attracted coverage from every major Slovak TV station and print media outlet on the day before the elections. Because of an electoral silence period, the train campaign was the only electoral content visible to citizens at that time. All money was raised through donations online, costing a total of only 30,000 Euro.

Reach Youth

In Hungary, Kispolgar Nonprofit LLC created a mobile app for kids called Kispolgar (“little citizen”), targeted at children aged 8 to 14. Designed to address the “news desert” facing children, the app aims to make daily news accessible, summarizing stories in a simple, entertaining way and providing definitions of terms and people. The aim is to build critical thinking skills, cognitive resilience against disinformation, and a future generation of informed citizens. The organization has more than 4,000 active users.

Also in Hungary, the Orban government has tightened control over the information environment for high school students and significantly restricted student life, with the ruling party seizing control of all student bodies. The organization, the Hungarian Civil Union, documented several negative outcomes from this action: teenagers becoming more isolated and lost online, the weakening of community ties, apathy and low participation in democracy, and a desire for most students to leave the country for a successful future.

In response, the Union set out to build a nonpartisan student network, identifying student government leaders to serve as mediators and change agents. Through games, polling, advocacy, and developing a student diplomats’ council, a thriving student community has been formed.

The project used data to design interventions. Through polling, the Union measured aspects of student life and identified specific challenges, as well as tested the success of interventions. The project also initiated a series of trainings for students, creating forums for engagement. The Union used retired diplomats to conduct several of these trainings, including in communications, diplomacy, and foreign affairs. The Union used a series of student contests and awards to draw student participation. A key component of the initiative was to connect Hungarian students to students from other EU countries. Through this engagement, the initiative organized the European Charter of Students’ Rights Workshop with eight countries

The Union considers its main success the ability to join the European student organization, Obessu. In Hungary, civic organizations struggle to be heard and visible under the current Orban regime. While Hungary was once a part of this organization, even serving as president, its membership was terminated decades ago. After the determination and advocacy of the student organization, OKE, Obessu recognized the importance of including students from autocratic societies. This has provided the opportunity for Hungarian students to attend events across Europe and invite EU students to Hungary.

The organizers point out that several challenges remain in building student engagement in public life and community in Hungary. In particular, participation in university groups and student life is low due to government control. Students’ abilities for self-organization and advocacy require constant development, including opportunities and institutional space to participate in democratic life. However, the Union points out the willingness of students to engage in recent protests as a positive development.

Lawyer Up

Ahead of the October 26, 2024, parliamentary elections in Georgia, the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party conducted a widespread campaign of intimidation and threats, vote buying, raids of civil society organizations, abuse of state resources, and confiscation of personal IDs. GD, in lockstep with the Kremlin, conducted a disinformation campaign, pushing narratives intended to scare voters with threats of war if they voted for the opposition and myths about a European and American “global war party” intent on hurting Georgia. On election day, independent election observers presented their findings and documentation describing serious irregularities, including multiple voting, ballot stuffing, lack of secrecy, intimidation, and statistical impossibilities. International observation missions declared the elections neither free nor fair.

GYLA reported violations:

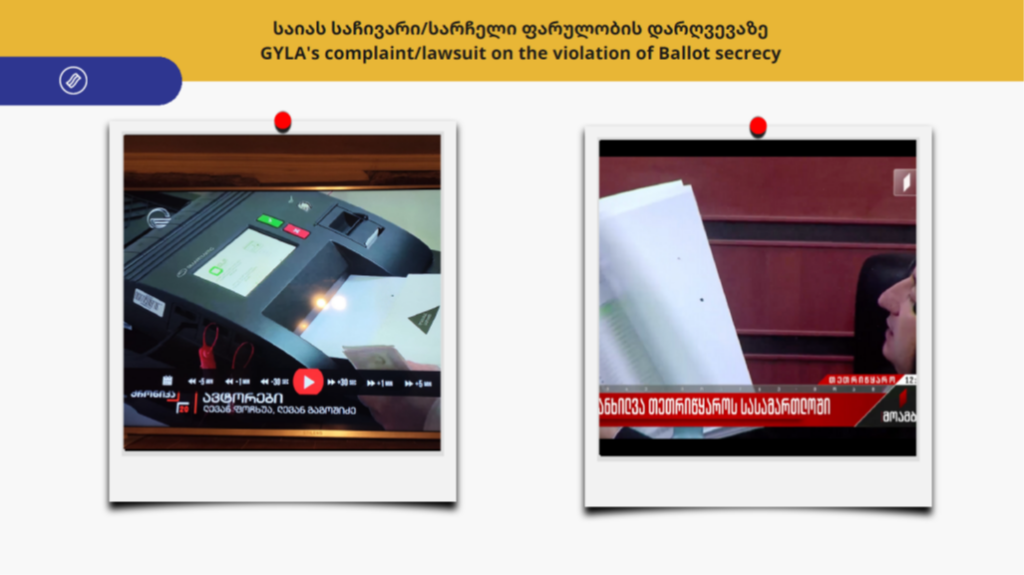

The Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA) served as election observers but also filed legal complaints. One indisputable violation of the elections witnessed and reported across the country was the lack of ballot secrecy. The circles voters had to fill out when selecting a party could be seen easily on the backside of the ballot, and given the placement of the ruling party and opposition parties, anyone could easily see the intention of the vote. Further, all polling stations had video cameras installed, directed at the counting machines, telegraphing voters’ selections beyond the polling station.

GYLA filed complaints in 73 electoral districts, 24 city and district courts, and two appeals courts seeking the annulment of approximately two million votes cast in precincts where electronic voting technologies were used. They argued that the secrecy of the ballot had been grossly violated due to the exposure of the voter’s choice on the reverse side of the ballot. Though a lower court judge ruled that secrecy was violated, the decision was overturned on appeal. GYLA lawyers relentlessly requested the appeals court to enact the voting procedure in the courtroom using the same machines to demonstrate the clear violation of secrecy. The court granted the motion, and judges themselves took part in the experiment. The entire trial lasted approximately 24 hours with only a few short breaks.

Despite a clear demonstration of the breach of secrecy, the cases were ultimately dismissed. The final ruling was so absurd, with a judge actually claiming he could not see anything, that it further fueled public outrage. By that time, a viral “dot” campaign was already underway as part of the ongoing protest movement. People wore black dots to symbolize the marking on the ballots that compromised secrecy. While the legal case was not successful, taking the government to court raised domestic and international awareness about the elections and subsequently led to international condemnation and sanctions.

Confrontation: Use Their Own Words

WSCHÓD is Poland’s largest youth-led movement advocating for “socially just transformations toward an economy that safeguards both people and the climate.” WSCHOD initiated a social media initiative called “confrontations,” where they address politicians with tough questions and record the encounter. They’ve employed this tactic with prominent Polish and European leaders, including President Andrzej Duda, President Emmanuel Macron, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, and Vice-President Frans Timmermans. The direct, unfiltered encounters have gone viral and generated widespread media attention, including from The New York Times and The Guardian, reaching millions and engendering public pressure.

In 2023, WISHOD spearheaded Poland’s most influential voter turnout campaign ahead of the national elections, reaching over 10 million people online and engaging thousands more in person through creative events like Poland’s first “silent disco” outside parliament. They conducted 2,000 voter interviews at the Open’er Festival, visited 16 swing cities during a two-week tour, held multiple press conferences, and mobilized thousands at turnout events. The advocacy efforts included launching six petitions that gathered over 70,000 signatures. The organization gained over 30,000 social media followers and grew its mailing list to more than 60,000 subscribers.

As part of the campaign, WISHOD gathered the sexist and misogynistic quotes from male politicians and put them in a video clip with women listening to and processing the remarks, watch here.

The viewer can see that the women look exasperated, agitated, despondent, and numb in varying degrees. Toward the end of the video, wanting to just stop the noise of these men, women slowly placed their finger over their lips to make the universal “shh” sign, but using their middle finger. The video had more than 14 million views ahead of the elections.

WISHOD’s main lessons learned from their campaigns for others: become a player, tell the untold story, confront those in power, do fun activities, and build an apolitical network.

Separate Church and State

The Congress of Catholic Women and Men was formed to remove politics from the church and the church from politics. According to polling, 82 percent of Poles believe the Church should remain neutral in politics, though this has not been the case, causing harm to the democratic process. In response, the Congress created a people-driven initiative to advocate for reform.

The Congress started by building public awareness about church politicization and how it serves as a tool for politicians. Through TikTok, podcasts, and YouTube clips, the organization outlined “20 steps” for church leaders and politicians to follow. The content emphasized healthy principles for state-church relations. The Congress also held numerous seminars and expert workshops. They also made over 72 interventions on violations of both civil and church laws, which require a clear separation. To bring attention to their campaign, the Congress challenged people to pose in photos with leaders and influencers holding the campaign poster.

Andrzej Zoll, Commissioner for Human Rights, Chairman of the National Election Commission, Chief Justice of the Constitutional Tribunal

Andrzej Zoll, Commissioner for Human Rights, Chairman of the National Election Commission, Chief Justice of the Constitutional Tribunal

The group gained more than one million TikTok followers and thousands of impressions on Instagram. The Congress estimates that more than 40 percent of Poles were reached through this initiative. The Congress attributes its success to building out networks of leaders and advocating the public benefits of delineation, in particular by emphasizing the abuse of principles on both sides.

Get Out of Town

The Civic Engagement and Activism Center in Georgia conducts civic and election awareness campaigns in ethnic Azeri minority communities. Ethnic minorities make up approximately 13 percent of the Georgian population but are quite isolated from political life. Many ethnic Azeris do not speak Georgian and receive the bulk of their news from inaccurate Russian, Iranian, Turkish, and Azerbaijani sources. As a result, according to public opinion research, this community is more likely to have anti-EU and anti-NATO sentiments, pro-Russian sympathies, and anti-democratic beliefs. Only 15 percent of Azeris believe that the dissolution of the Soviet Union was a “good thing.” More than half of the Azeri respondents do not know the name of the country’s prime minister.

While Russian interference has been well documented in Georgia, in Azeri minority communities, Iranian proxies fund local religious organizations, mosques, madrasas, media outlets, NGOs, research centers, businesses, and charities, and these groups have been actively involved during the electoral campaign period in 2024 spreading disinformation about the elections as well as anti-Western, anti-LGBTQ narratives, coinciding with ruling regime messaging. Azerbaijani political leaders and media figures appeared side by side with candidates, repeating anti-Western narratives and warning of “war” if the opposition was elected.

To address low political engagement and awareness – and to counter disinformation campaigns- the Civic Engagement and Activism Center visited 100 villages in one month ahead of the 2024 elections to discuss elections, reaching thousands of people. As part of the campaign, the organization created and shared 12 videos on the European Union and what membership would mean for Georgia, as well as four educational television shows. Further, the initiative organized town hall meetings for the political parties to share their vision with citizens and answer questions. On election day, nearly 30 members of the Civic Engagement and Activism Center observed the voting process across various polling stations. The organization’s members also distributed an informational newspaper in the Azerbaijani language to raise awareness and encourage informed participation.

A representative from the Center explained how years of neglect by politicians, government officials, Western-funded GONGOs (government-organized non-governmental organizations) groups, and mainstream NGOs have created a vacuum for nefarious and anti-democratic forces to fill. More engagement with marginalized and isolated communities is essential to fend off democratic declines in the country.

Also in Georgia, the independent media outlet Batumelebi focuses on stories that are close to the people, prioritizing local voices and issues. Their journalists regularly travel to remote and rural areas (including across the Russian occupation line) to meet with citizens and report on their everyday lives. Coverage spans a wide range of topics – from highway safety and education to forest management and local council legislation.

Batumelebi also produces short documentaries, such as one highlighting the lives of women in the mountainous Adjara region. But their work goes beyond reporting: they provide a platform for local residents to express their views on major national issues, including security, international relations, legislative initiatives, and political reforms. This approach allows communities, often feeling disconnected or abandoned by the political center, to have their voices heard and perspectives represented.

As a result, Batumelebi has built strong trust among these communities. Citizens are not only engaged but also frequently become sources of information themselves, even in highly repressive environments. This deep connection with the local population has led to the exposure of numerous systemic issues, including deficits in education, lack of access to healthcare, particularly for women, infrastructure and disaster management failures, signs of corruption in public procurement, and more. Their reporting has raised awareness and contributed to calls for urgent policy changes.

Scenario Planning in Autocratic Settings: Lessons Learned

To help brainstorm effective responses to autocratic tactics, participants were divided into tables by country. Through the app NewsQuest, each country table received a scenario based on a real or possible political development in another country, and then was prompted with a series of options for response, followed by escalating developments. The aim was to balance complex — and often conflicting — priorities to achieve success in three areas. Success in one area, such as resistance through protesting, could hurt another area, like organizational stability.

The Georgian team received the Hungarian scenario, starting with the scenario: “The government rushes through a new law banning LGBTQ+ Pride marches, citing ‘child protection’. Within hours, police begin warning organizers, and social media explodes with outrage.” The Georgian team was to envision themselves as a civic group and respond to a series of situations and action choices. For example, they are asked whether they should post a viral video encouraging people to join the street protest, or wait and focus on voter mobilization for a later election. The team was then prompted with an escalation – police cracking down on Pride protestors – and asked how they would respond with a series of choices. At the end of the game, the team is ranked on their success in the three change measurements: resistance against the regime, opposition unity, and chances for regime change.

The Hungarian team played the Slovak scenario, starting with, “The prime minister’s recent visit to Moscow sparks outrage. Critics say it signals a dangerous shift in foreign policy and democratic values.” They were then asked to choose between protesting and issuing a statement. As the scenario escalated to the government passing a foreign agents law, players had to decide between challenging the law in court or occupying a government building. Success was measured by government instability, social peace, and social support.

The Polish team played the Georgian scenario, starting with the actual development: “In 2024, Georgia’s ruling party passes the ‘Transparency of Foreign Influence’ law, targeting NGOs funded from abroad. The goal: stigmatize and control civil society.” The conflicting measurements of success included NGO operational stability, NGO support, and international support. Players were asked to choose between compliance and resistance after a series of escalating government measures.

Finally, the Slovakian team played the Polish scenario: “During the 2023 election campaign, Poland’s state-run media heavily favored the ruling party and portrayed opposition leaders and civil society groups as dangerous or foreign-backed. Many pro-democracy activists and NGOs were labeled as traitors or anti-Polish.” Players had to navigate tricky measures of success: opposition poll advantage, trust in NGOs, and NGO integrity, and were asked questions such as whether they (as an independent NGO) should participate in a debate on opposition-affiliated TV.

After each tabletop exercise, the teams presented their findings and received feedback from the country whose scenario they were playing. A key conflict identified across all scenarios was one of self-protectionism versus more active resistance. Participants agreed based on shared experiences that silence and capitulation only strengthen autocrats, while taking risks, even if it puts the security of the organization in danger, is needed. Further, if an organization remains silent, it still does not protect them in the long run. For civil society, exercising their voice is the main source of power and unlocks courage in others. A few participants added that strategies would vary based on the nature of the organization. For example, a legal rights organization, like the participant from the Georgian Young Lawyers Association, would focus on legal challenges, while journalists might do a short documentary. However, compliance with illegitimate or discriminatory rulings or policies was deemed a recipe for failure, and collective action was the only pathway to success.

For a second scenario exercise, participants formed three mixed country tables to identify a concrete challenge facing democrats in autocratic settings. One table selected the challenge of building collaboration and coalitions, seeing past conflict of interests and egos. Another table took on financial stability, given the lack of public funding, limited international support, and poor donation culture. The third table identified the challenge of offline and online communication in closed media environments – how to reach and understand target audiences. Following a clear mapping of the challenge, participants then moved to another table to work on solutions to the identified challenge by that table. Following this, participants move to the final table to map out an action plan. This cross-country brainstorming resulted in several innovative and creative solutions, and participants were able to learn from other countries’ experiences and expertise, what has worked and what has not.

Conclusion

There are many explanations for democracy’s decline. It has failed to deliver equitable economic growth, represent citizens’ needs adequately, and provide equal justice. Publics increasingly believe that their governing systems favor elites with financial power through overt corruption or legal influence avenues. These publics consequently exhibit rising distrust of government and perceive politicians and political parties, gatekeepers to power, as self-interested and unrepresentative. That most party officials and candidates are old, male, rich, and from a dominant ethnic and religious group compounds the problem.

Cultural divisions and polarization on traditional-values issues, such as those relevant to women’s rights, immigration, the LGBTQ+ community, and the role of religion, also challenge democracy. Many see cultural changes as threats to hierarchies of power and gravitate toward the transgressive political leader. Tapping into these cleavages, malign forces internally and externally propose alternative governance models. Right-wing authoritarianism is increasing in many countries, with citizens embracing the view that having a strong leader willing to “fight” is more important than protecting individual rights and democratic principles. Fear of others, change, and difference makes the simple solutions that illiberal populists promise alluring. Rising domestic authoritarians also have external support, forming alliances and receiving financing from foreign actors aiming to degrade democracy worldwide.

The playbook is unoriginal: dismantle government agencies and oversight bodies (anti-corruption, ombudsperson, inspectors general), limit the rights of marginalized communities and immigrants, restructure education and attack universities, interfere in the judiciary and appointment of judges, enrich donors and oligarchs over competitive processes, pass legislation limiting civil society organizations, block or shut down independent media, and thwart the election process.

Democrats need to align as autocrats have, supporting one another to fend off these steps in the playbook. Democracy activists from autocracies can help countries at the beginning of the backsliding process with foresight and scenario planning – to prepare for what’s next. We need to develop a democracy playbook and community of best practices to inspire and support others, leveraging the innovations and successes, such as those described in this report.