Prevention is an alternative approach to combatting terrorism. Prevention works to build resiliency in individuals and communities and halt the ideology that may lead to violence by addressing the early risk factors of radicalization and reducing the chance of violence before it occurs. Radicalization to violence is described as a process in which “an individual comes to believe, for a variety of reasons, that the threat or use of unlawful violence is necessary – or even justified – to accomplish a goal”.[1]

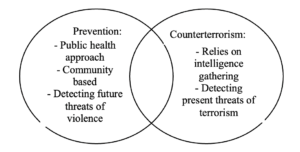

Prevention uses a public health and community-based approach to detect where future threats may occur, whereas counterterrorism focuses on detecting and thwarting violent acts of terrorism through intelligence gathering.

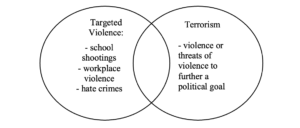

Targeted violencefers to “any incident of violence against a specific target based on perceived ideologies, which can be carried out by lone offenders or by individuals belonging to one or more hate groups.”[2] This category includes terrorism, mass shootings, and hate crimes.[3]

The Department of Homeland Security defines risk factors as “characteristic that may make an individual more susceptible to recruitment by violent extremist organizations and movements and may be addressed through prevention activities”.[4] In terms of radicalization, some risk factors can be a criminal history, sporadic work history, social isolation, and distance from one’s family.[5] It is important to note that identifying with one or more risk factors does not guarantee an individual will partake in mobilized violence.

On the other hand, protective factors are positive influences that improve one’s quality of life, reducing the chances of risk factors occurring. Protective factors are strong community ties and exposure to diverse thinking.

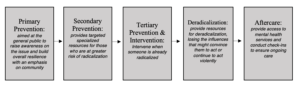

Preventative approaches to combatting violence can best be conceptualized as a timelinef progression points in which mobilized violence can be intercepted. This follows a public health model, moving from primary prevention action items to secondary and tertiary prevention action items, concluding with aftercare. Additionally, the CDC’s Division of Violence Prevention argues that different forms of violence share common risk and protective factors, emphasizing the impact that violence prevention efforts can have on violence at large.[6]

Primary prevention is geared toward the general public and centers on building resilience at large. Secondary prevention identifies vulnerable communities who are at greater risk of radicalization and caters resources specific to their needs. Tertiary prevention and intervention is another layer that involves intervention for those who are already radicalized. Deradicalization follows this step by removing the influences that might convince them to act violently. Finally, aftercare ensures ongoing support.

The McCain Institute’s Preventing Targeted Violence team centralizes prevention in their actions to combat violent extremism. This is done through three main initiatives: student innovation challenges, a prevention practitioners’ network, and a National Policy Blueprint to End White Supremacist Violence. Student innovation challenges empower students to create their own products or tools to address targeted violence. The prevention practitioners’ network gathers interdisciplinary professionals into a central location, and the National Policy Blueprint to End White Supremacy partnered with the Center for American Progress to create and enact federal reforms. These programs raise awareness, build resiliency, and centralizes a community focus.

Although there is some debate as to when prevention efforts began, there was a clear move to push this approach in 2011 when President Obama released his “Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States” strategy.[7] The goal of this strategy was to “prevent violent extremists and their supporters from inspiring, radicalizing, financing, or recruiting individuals or groups in the United States to commit acts of violence”.[8] This would be done through supporting local communities, improving relationships between government and vulnerable communities, and countering extremist propaganda.[9]

The future of preventiones in the openness of the government to implement preventative initiatives beyond their current work.

In May of this year, the Department of Homeland Security replaced their Office for Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention with the Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships or CP3.[10] CP3’s mission is to bring an “approach to violence prevention that leverages behavioral threat assessment and management tools, and addresses early-risk factors that can lead to radicalization to violence”.[11] They accomplish this in five teams of “Policy and Research, Prevention Education, Strategic Engagement, Grants and Innovation, and Field Operations”.[12]

Additionally, the White House’s National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism displays government support for expanding prevention efforts and including it as a priority in deterring terrorism threats.

In order to successfully combat terrorism and targeted violence, a preventative approach is needed. Prevention works to detect future threats of violence by strengthening communities and bringing positive public health approaches to the field. The future of counterterrorism looks toward implementing more preventative strategies to better reduce violence.

[1] “Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships.” Department of Homeland Security, November 12, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/CP3.

[2] “Preventing Targeted Violence.” McCain Institute, October 29, 2021. https://www.mccaininstitute.org/programs/preventing-targeted-violence/.

[3] “Preventing Targeted Violence.” McCain Institute, October 29, 2021. https://www.mccaininstitute.org/programs/preventing-targeted-violence/.

[4] FAQ Sheet: What Are Risk Factors and Indicators? Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/risk_factors_and_indicators_infosheet.pdf.

[5] FAQ Sheet: What Are Risk Factors and Indicators? Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/risk_factors_and_indicators_infosheet.pdf.

[6] Preventing Multiple Forms of Violence: A Strategic Vision for Connecting the Dots. Atlanta, GA: Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016.

[7] Clifford, Bennett, Seamus Hughes, and Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens. “An Abridged History of America’s Terrorism Prevention Programs: Fits and Starts.” Lawfare, January 7, 2021. https://www.lawfareblog.com/abridged-history-americas-terrorism-prevention-programs-fits-and-starts.

[8] Rep. Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States . The White House, August 2011. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/empowering_local_partners.pdf.

[9] Rep. Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States . The White House, August 2011. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/empowering_local_partners.pdf.

[10] “Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships.” Department of Homeland Security, November 12, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/CP3.

[11] “Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships.” Department of Homeland Security, November 12, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/CP3.

[12] “Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships.” Department of Homeland Security, November 12, 2021. https://www.dhs.gov/CP3.